dispersion of the values of a random variable around its expected value

Videos

[SOLVED by u/BurkeyAcademy]

Hello, could you review the following logic:

I designed an item with a length of 5.00 metre. After manufacturing, I collected data of hundreds of lengths of the item:

Mean = 5.10m (i.e. average 0.10m longer) Standard deviation = 0.30m

My view is that we cannot trust the 0.10m value, because the standard deviation is 0.30m. However, I looked up how to justify variability, and found Coefficient of Variability (CV) which is based on SD/mean.

Also, are there any way I can assess SD against the 0.10m value?

As other users have mentioned in the comments, "small" and "large" are arbitrary and depend on the context. However, one very simple way to think about whether a standard deviation is small or large is as follows. If you assume that your data is normally distributed, then approximately 68% of your data points fall between one standard deviation below the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean. In the case of your data, this would mean 68% of students scored between roughly 63 and 95, and conversely 32% scored either above 95 or below 63. This gives a practical way to understand what your standard deviation is telling you (again, under the assumption that your data is normal). If you would have expected a greater percentage to fall between 63 and 95, then your standard deviation may be considered large, and if you would have expected a smaller percentage, then your standard deviation may be considered small.

I believe that standard deviation is a tool to compare two data sets or more. Thus, the higher standard deviation of dataset will be the one considered large where data are more spread-out in relationships to the mean. On the other hand, a lower standard deviation will be considered small.

Also, it is a tool to evaluate how the numbers are spread-out from one data set.

the standard deviation could be considered big or small based on whatever reason the data set is serving. Example salaries of entry-level jobs, run-time of one mile for a particular sport team. for the sport team, you may have one athlete that is way faster than the others. Thus, we can use standard deviation to see how far he is above the mean. bottom line. it depends on how you want to use your data. If you think it is small, it is small. if you think it is big, it i

Discussion of the new question:

For example, if I want to study human body size and I find that adult human body size has a standard deviation of 2 cm, I would probably infer that adult human body size is very uniform

It depends on what we're comparing to. What's the standard of comparison that makes that very uniform? If you compare it to the variability in bolt-lengths for a particular type of bolt that might be hugely variable.

while a 2 cm standard deviation in the size of mice would mean that mice differ surprisingly much in body size.

By comparison to the same thing in your more-uniform humans example, certainly; when it comes to lengths of things, which can only be positive, it probably makes more sense to compare coefficient of variation (as I point out in my original answer), which is the same thing as comparing sd to mean you're suggesting here.

Obviously the meaning of the standard deviation is its relation to the mean,

No, not always. In the case of sizes of things or amounts of things (e.g. tonnage of coal, volume of money), that often makes sense, but in other contexts it doesn't make sense to compare to the mean.

Even then, they're not necessarily comparable from one thing to another. There's no applies-to-all-things standard of how variable something is before it's variable.

and a standard deviation around a tenth of the mean is unremarkable (e.g. for IQ: SD = 0.15 * M).

Which things are we comparing here? Lengths to IQ's? Why does it make sense to compare one set of things to another? Note that the choice of mean 100 and sd 15 for one kind of IQ test is entirely arbitrary. They don't have units. It could as easily have been mean 0 sd 1 or mean 0.5 and sd 0.1.

But what is considered "small" and what is "large", when it comes to the relation between standard deviation and mean?

Already covered in my original answer but more eloquently covered in whuber's comment -- there is no one standard, and there can't be.

Some of my points about Cohen there still apply to this case (sd relative to mean is at least unit-free); but even with something like say Cohen's d, a suitable standard in one context isn't necessarily suitable in another.

Answers to an earlier version

We always calculate and report means and standard deviations.

Well, maybe a lot of the time; I don't know that I always do it. There's cases where it's not that relevant.

But what does the size of the variance actually mean?

The standard deviation is a kind of average* distance from the mean. The variance is the square of the standard deviation. Standard deviation is measured in the same units as the data; variance is in squared units.

*(RMS -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Root_mean_square)

They tell you something about how "spread out" the data are (or the distribution, in the case that you're calculating the sd or variance of a distribution).

For example, assume we are observing which seat people take in an empty room. If we observe that the majority of people sit close to the window with little variance,

That's not exactly a case of recording "which seat" but recording "distance from the window". (Knowing "the majority sit close to the window" doesn't necessarily tell you anything about the mean nor the variation about the mean. What it tells you is that the median distance from the window must be small.)

we can assume this to mean that people generally prefer siting near the window and getting a view or enough light is the main motivating factor in choosing a seat.

That the median is small doesn't of itself tell you that. You might infer it from other considerations, but there may be all manner of reasons for it that we can't in any way discern from the data.

If on the other hand we observe that while the largest proportion sit close to the window there is a large variance with other seats taken often also (e.g. many sit close to the door, others sit close to the water dispenser or the newspapers), we might assume that while many people prefer to sit close to the window, there seem to be more factors than light or view that influence choice of seating and differing preferences in different people.

Again, you're bringing in information outside the data; it might apply or it might not. For all we know the light is better far from the window, because the day is overcast or the blinds are drawn.

At what values can we say that the behavior we have observed is very varied (different people like to sit in different places)?

What makes a standard deviation large or small is not determined by some external standard but by subject matter considerations, and to some extent what you're doing with the data, and even personal factors.

However, with positive measurements, such as distances, it's sometimes relevant to consider standard deviation relative to the mean (the coefficient of variation); it's still arbitrary, but distributions with coefficients of variation much smaller than 1 (standard deviation much smaller than the mean) are "different" in some sense than ones where it's much greater than 1 (standard deviation much larger than the mean, which will often tend to be heavily right skew).

And when can we infer that behavior is mostly uniform (everyone likes to sit at the window)

Be wary of using the word "uniform" in that sense, since it's easy to misinterpret your meaning (e.g. if I say that people are "uniformly seated about the room" that means almost the opposite of what you mean). More generally, when discussing statistics, generally avoid using jargon terms in their ordinary sense.

and the little variation our data shows is mostly a result of random effects or confounding variables (dirt on one chair, the sun having moved and more shade in the back, etc.)?

No, again, you're bringing in external information to the statistical quantity you're discussing. The variance doesn't tell you any such thing.

Are there guidelines for assessing the magnitude of variance in data, similar to Cohen's guidelines for interpreting effect size (a correlation of 0.5 is large, 0.3 is moderate, and 0.1 is small)?

Not in general, no.

Cohen's discussion[1] of effect sizes is more nuanced and situational than you indicate; he gives a table of 8 different values of small medium and large depending on what kind of thing is being discussed. Those numbers you give apply to differences in independent means (Cohen's d).

Cohen's effect sizes are all scaled to be unitless quantities. Standard deviation and variance are not -- change the units and both will change.

Cohen's effect sizes are intended to apply in a particular application area (and even then I regard too much focus on those standards of what's small, medium and large as both somewhat arbitrary and somewhat more prescriptive than I'd like). They're more or less reasonable for their intended application area but may be entirely unsuitable in other areas (high energy physics, for example, frequently require effects that cover many standard errors, but equivalents of Cohens effect sizes may be many orders of magnitude more than what's attainable).

For example, if 90% (or only 30%) of observations fall within one standard deviation from the mean, is that uncommon or completely unremarkable?

Ah, note now that you have stopped discussing the size of standard deviation / variance, and started discussing the proportion of observations within one standard deviation of the mean, an entirely different concept. Very roughly speaking this is more related to the peakedness of the distribution.

For example, without changing the variance at all, I can change the proportion of a population within 1 sd of the mean quite readily. If the population has a $t_3$ distribution, about 94% of it lies within 1 sd of the mean, if it has a uniform distribution, about 58% lies within 1 sd of the mean; and with a beta($\frac18,\frac18$) distribution, it's about 29%; this can happen with all of them having the same standard deviations, or with any of them being larger or smaller without changing those percentages -- it's not really related to spread at all, because you defined the interval in terms of standard deviation.

[1]: Cohen J. (1992),

"A power primer,"

Psychol Bull., 112(1), Jul: 155-9.

By Chebyshev's inequality we know that probability of some $x$ being $k$ times $\sigma$ from mean is at most $\frac{1}{k^2}$:

$$ \Pr(|X-\mu|\geq k\sigma) \leq \frac{1}{k^2} $$

However with making some distributional assumptions you can be more precise, e.g. Normal approximation leads to 68–95–99.7 rule. Generally using any cumulative distribution function you can choose some interval that should encompass a certain percentage of cases. However choosing confidence interval width is a subjective decision as discussed in this thread.

Example

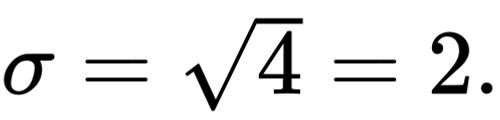

The most intuitive example that comes to my mind is intelligence scale. Intelligence is something that cannot be measured directly, we do not have direct "units" of intelligence (by the way, centimeters or Celsius degrees are also somehow arbitrary). Intelligence tests are scored so that they have mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. What does it tell us? Knowing mean and standard deviation we can easily infer which scores can be regarded as "low", "average", or "high". As "average" we can classify such scores that are obtained by most people (say 50%), higher scores can be classified as "above average", uncommonly high scores can be classified as "superior" etc., this translates to table below.

Wechsler (WAIS–III) 1997 IQ test classification IQ Range ("deviation IQ")

IQ Classification 130 and above Very superior 120–129 Superior 110–119 High average 90–109 Average 80–89 Low average 70–79 Borderline 69 and below Extremely low(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IQ_classification)

So standard deviation tells us how far we can assume individual values be distant from mean. You can think of $\sigma$ as of unitless distance from mean. If you think of observable scores, say intelligence test scores, than knowing standard deviations enables you to easily infer how far (how many $\sigma$'s) some value lays from the mean and so how common or uncommon it is. It is subjective how many $\sigma$'s qualify as "far away", but this can be easily qualified by thinking in terms of probability of observing values laying in certain distance from mean.

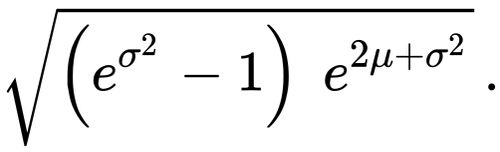

This is obvious if you look on what variance ($\sigma^2$) is

$$ \operatorname{Var}(X) = \operatorname{E}\left[(X - \mu)^2 \right]. $$

...the expected (average) distance of $X$'s from $\mu$. If you wonder, than here you can read why is it squared.