Videos

I help a friend who has a hobby store with his simple, one-page website. I really don't know much about web hosting. A week ago the hosting company sent an email saying the SSL cert was going to expire. I asked via email what I needed to do and they said it will be fixed. Today I got an email from them asking if I was satisfied with their handling of my question. Nothing that said they did anything.

How can I verify it is fixed?

Yes, you can use openssl to create a test server for your certificate with the s_server command. This creates a minimal SSL/TLS server that responds to HTTP requests on port 8080:

openssl s_server -accept 8080 -www -cert yourcert.pem -key yourcert.key -CAfile chain.pem

yourcert.pem is the X.509 certificate, yourcert.key is your private key and chain.pem contains the chain of trust between your certificate and a root certificate. Your CA should have given you yourcert.pem and chain.pem.

Then use openssl's s_client to make a connection:

openssl s_client -connect localhost:8080 -showcerts -CAfile rootca.pem

or on Linux:

openssl s_client -connect localhost:8080 -showcerts -CApath /etc/ssl/certs

Caution: That command doesn't verify that the host name matches the CN (common name) or SAN (subjectAltName) of your certificate. OpenSSL doesn't have a routine for the task yet. It's going to be added in OpenSSL 1.1.

The best and easiest way to validate the SSL issued by your CA is to decode it.

Here is a helpful link the will help you do that: http://www.sslshopper.com/csr-decoder.html

Hope this helps!

Here is a very simplified explanation:

Your web browser downloads the web server's certificate, which contains the public key of the web server. This certificate is signed with the private key of a trusted certificate authority.

Your web browser comes installed with the public keys of all of the major certificate authorities. It uses this public key to verify that the web server's certificate was indeed signed by the trusted certificate authority.

The certificate contains the domain name and/or ip address of the web server. Your web browser confirms with the certificate authority that the address listed in the certificate is the one to which it has an open connection.

Browser and server calculate a shared symmetric key which is used for the actual data encryption. Since the server identity is verified the client can be sure, that this "key exchange" is done with the right server and not some man in the middle attacker.

Note that the certificate authority (CA) is essential to preventing man-in-the-middle attacks. However, even an unsigned certificate will prevent someone from passively listening in on your encrypted traffic, since they have no way to gain access to your shared symmetric key.

You said that

the browser gets the certificate's issuer information from that certificate, then uses that to contact the issuerer, and somehow compares certificates for validity.

The client doesn't have to check with the issuer because two things :

- all browsers have a pre-installed list of all major CAs public keys

- the certificate is signed, and that signature itself is enough proof that the certificate is valid because the client can make sure, on his own, and without contacting the issuer's server, that that certificate is authentic. That's the beauty of asymmetric encryption.

Notice that 2. can't be done without 1.

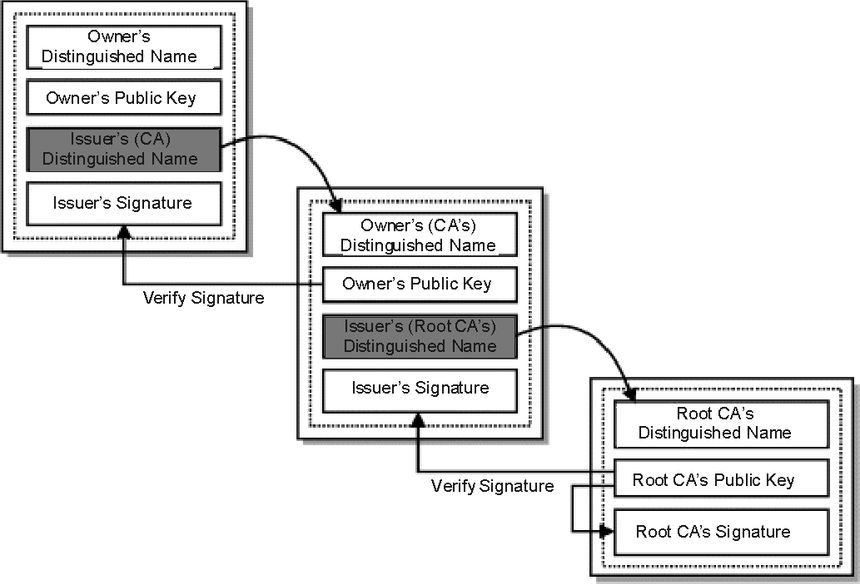

This is better explained in this big diagram I made some time ago

(skip to "what's a signature ?" at the bottom)

You are correct that SSL uses an asymmetric key pair. One public and one private key is generated which also known as public key infrastructure (PKI). The public key is what is distributed to the world, and is used to encrypt the data. Only the private key can actually decrypt the data though. Here is an example:

Say we both go to walmart.com and buy stuff. Each of us get a copy of Walmart's public key to sign our transaction with. Once the transaction is signed by Walmart's public key, only Walmart's private key can decrypt the transaction. If I use my copy of Walmart's public key, it will not decrypt your transaction. Walmart must keep their private key very private and secure, else anyone who gets it can decrypt transactions to Walmart. This is why the DigiNotar breach was such a big deal

Now that you get the idea of the private and public key pairs, it's important to know who actually issues the cert and why certs are trusted. I'm oversimplifying this, but there are specific root certificate authorities (CA) such as Verisign who sign certs, but also sign for intermediary CA's. This follows what is called Chain of Trust, which is a chain of systems that trust each other. See the image linked below to get a better idea (note the root CA is at the bottom).

Organizations often purchase either wildcard certs or get registered as a intermediate CA themselves who is authorized to sign for their domain alone. This prevents Google from signing certs for Microsoft.

Because of this chain of trust, a certificate can be verified all the way to the root CA. To show this, DigiCert (and many others) have tools to verify this trust. DigiCert's tool is linked here. I did a validation on gmail.com and when you scroll down it shows this:

This shows that the cert for gmail.com is issued by Google Internet Authority G2, who is in turn issued a cert from GeoTrust Global, who is in turn issued a cert from Equifax.

Now when you go to gmail.com, your browser doesn't just get a blob of a hash and goes on it's way. No, it gets a whole host of details along with the cert:

These details are what your browser uses to help identify the validity of the cert. For example, if the expiration date has passed, your browser will throw a cert error. If all the basic details of the cert check out, it will verify all the way to the root CA, that the cert is valid.

Now that you have a better idea as to the cert details, this expanded image similar to the first one above will hopefully make more sense:

This is why your browser can verify one cert against the next, all the way to the root CA, which your browser inherently trusts.

To clarify one point from the question not covered in the otherwise excellent answer by @PTW-105 (and asked in the comment there by @JVE999):

I thought public key is to encrypt data, not to decrypt data...

The keys work both ways - what is encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the private and vice versa. We just decide one is private and one is public, there's no conceptual difference.

So if I encrypt data to send to you I use your public key to encrypt it and only you can decrypt it with your private key.

However, if I want to sign something, to prove it came from me, then I generate a hash of the message and encrypt that hash with my private key. Then anyone can decrypt it with my public key and compare to the actual message hash, but they know that only I could have encrypted it, since only I have my private key. So they know the message hash hasn't changed since I signed it, and therefore that it came from me.

As per the comments, the above is not quite true. See the link from the comment by @dave_thompson_085. However, this isn't a "how to sign properly" tutorial, just clarifying the roles of private and public keys in encryption verses signing. The basic point in that regard is this:

- To encrypt data the external party uses a public key and only the private key holder can decrypt it.

- To sign, the private key holder uses a hash function and their private key (plus appropriate padding, etc.). The external party can then verify the signature using the public key. This ensures the message came from the private key holder (assuming no-one else has access to the private key).

Signing may sometimes (depending on the implementation) be done with the same key pair as encryption, just used the other way round, or it may use a distinct key pair (see another link, also from @dave_thompson_085's comment)

Generally what this means is that OpenSSL's default CA path doesn't contain the certificate that signed the one you're checking - usually an intermediate certificate.

You'll need to get a copy of the intermediate (most CAs will provide, or you can fetch it from an SSL connection whose trust is working), and point at it in your openssl command with -CAfile intermediate.pem.

You should be able to download from your provider all the certificates that form the chain of trust from you signed certificate up to the signing Certificate Authority.

Then use openssl verify using those certs. Check both the -CAfile and the -CApath options of the verify(1) command to learn how.

Assuming your certificates are in PEM format, you can do:

openssl verify cert.pem

If your "ca-bundle" is a file containing additional intermediate certificates in PEM format:

openssl verify -untrusted ca-bundle cert.pem

If your openssl isn't set up to automatically use an installed set of root certificates (e.g. in /etc/ssl/certs), then you can use -CApath or -CAfile to specify the CA.

Here is one-liner to verify a certificate chain:

openssl verify -verbose -x509_strict -CAfile ca.pem -CApath nosuchdir cert_chain.pem

This doesn't require to install CA anywhere.

See https://stackoverflow.com/questions/20409534/how-does-an-ssl-certificate-chain-bundle-work for details.

Update

As noted by Klaas van Schelven, the answer above is misleading as openssl appears to verify only single top certificate per file. So it's necessary to issue multiple verify commands for each certificate chain node placed in separate file.