Your current method covers the first point - to take an exception as parameter.

The throws Exception is unnecessary if you dont throw it from a method, but it is needed to cover the second point.

As commenters pointed, you just need to use the throw keyword to throw an exception, so the method could look like:

public void throwException (Exception ex) throws Exception {

//some other code maybe?

throw ex;

}

This implementation has a little flaw. When the null is passed as a parameter to it, the method will throw a NullPointerException, because the throw keyword accepts objects of the Throwable class or its subclasses (Exception is a subclass of Throwable).

To avoid NullPointerException (which is an unchecked-exception), simple if statement can be used:

public void throwException (Exception ex) throws Exception {

if (ex != null) {

throw ex;

}

//just for presentation,below it throws new Exception

throw new Exception("ex parameter was null");

}

Edit:

As @Slaw suggested, in that very small case adding the null-check and throwing new Exception just disguises the NullPointerException. Without the null-check and throw new... the NPE will be thrown from that method and its stacktrace will show exact line of throw ex when the null is passed to that method.

The NPE is a subtype of RuntimeException class and the subtypes of RuntimeException doesn't need to be explicitly declared in method signature when they are thrown from that method. Like here:

public static void throwNPE(Exception e) {

throw new NullPointerException();

}

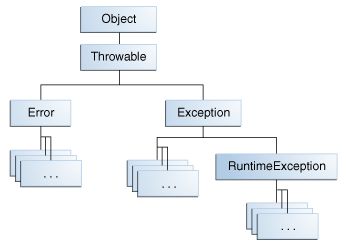

The RuntimeException and its subclasses are called an unchecked-exceptions. Other classes extending one of Exception or Throwable classes are call checked-exceptions, because if a method throws them, it must declare that exception (or superclass) in the signature or explicitly try-catch it.

The proper use of null-check would be when the method would throw a more specific kind of exception (like IOException or a new subclass of Exception/Throwable) and the when the other method using the one which throws that new type of Exception would try-catch that specific type the NPE wouldn't be caught.

Just for good practices, when dealing with try-catch it's much better to catch exact types of thrown Exceptions instead of general Exception/Throwable. It helps to understand the real cause of exception, debug and fix code.

Answer from itwasntme on Stack OverflowWhat does Throwing an exception mean?

java - Why is "throws Exception" necessary when calling a function? - Stack Overflow

Result object vs throwing exceptions

java - How to manage exceptions in a long call stack - Software Engineering Stack Exchange

Videos

I understand try, catch, and finally. But what does throw mean and how would i use it?

In Java, as you may know, exceptions can be categorized into two: One that needs the throws clause or must be handled if you don't specify one and another one that doesn't. Now, see the following figure:

In Java, you can throw anything that extends the Throwable class. However, you don't need to specify a throws clause for all classes. Specifically, classes that are either an Error or RuntimeException or any of the subclasses of these two. In your case Exception is not a subclass of an Error or RuntimeException. So, it is a checked exception and must be specified in the throws clause, if you don't handle that particular exception. That is why you needed the throws clause.

From Java Tutorial:

An exception is an event, which occurs during the execution of a program, that disrupts the normal flow of the program's instructions.

Now, as you know exceptions are classified into two: checked and unchecked. Why these classification?

Checked Exception: They are used to represent problems that can be recovered during the execution of the program. They usually are not the programmer's fault. For example, a file specified by user is not readable, or no network connection available, etc., In all these cases, our program doesn't need to exit, instead it can take actions like alerting the user, or go into a fallback mechanism(like offline working when network not available), etc.

Unchecked Exceptions: They again can be divided into two: Errors and RuntimeExceptions. One reason for them to be unchecked is that they are numerous in number, and required to handle all of them will clutter our program and reduce its clarity. The other reason is:

Runtime Exceptions: They usually happen due to a fault by the programmer. For example, if an

ArithmeticExceptionof division by zero occurs or anArrayIndexOutOfBoundsExceptionoccurs, it is because we are not careful enough in our coding. They happen usually because some errors in our program logic. So, they must be cleared before our program enters into production mode. They are unchecked in the sense that, our program must fail when it occurs, so that we programmers can resolve it at the time of development and testing itself.Errors: Errors are situations from which usually the program cannot recover. For example, if a

StackOverflowErroroccurs, our program cannot do much, such as increase the size of program's function calling stack. Or if anOutOfMemoryErroroccurs, we cannot do much to increase the amount of RAM available to our program. In such cases, it is better to exit the program. That is why they are made unchecked.

For detailed information see:

- Unchecked Exceptions — The Controversy

- The Catch or Specify Requirement

Java requires that you handle or declare all exceptions. If you are not handling an Exception using a try/catch block then it must be declared in the method's signature.

For example:

class throwseg1 {

void show() throws Exception {

throw new Exception();

}

}

Should be written as:

class throwseg1 {

void show() {

try {

throw new Exception();

} catch(Exception e) {

// code to handle the exception

}

}

}

This way you can get rid of the "throws Exception" declaration in the method declaration.

You have to distinguish between return values and errors.

A return value is one of many possible outcomes of a computation. An error is an unexpected situation which needs to be reported to the caller.

A module may indicate that an error occurred with a special return value or it throws an exception because an error was not expected. That errors occur should be an exception, that's why we call them exceptions.

If a module validates lottery tickets, the outcome may be:

- you have won

- you have not won

- an error occurred (e.g. the ticket is invalid)

In case of an error, the return value is neither "won" nor "not won", since no meaningful statement can be made when e.g. the lottery ticket is not valid.

Addendum

One might argue that invalid tickets are a common case and not an error. Then the outcome of the ticket validation will be:

- you have won

- you have not won

- the ticket is invalid

- an error occurred (e.g. no connection to the lottery server)

It all depends on what cases you are planning to support and what are unexpected situations where you do not implement logic other than to report an error.

This is a good question that professional developers have to consider carefully. The guideline to follow is that exceptions are called exceptions because they are exceptional. If a condition can be reasonably expected then it should not be signaled with an exception.

Let me give you a germane example from real code. I wrote the code which does overload resolution in the C# compiler, so the question I faced was: is it exceptional for code to contain overload resolution errors, or is it reasonably expected?

The C# compiler's semantic analyzer has two primary use cases. The first is when it is "batch compiling" a codebase for, say, a daily build. The code is checked in, it is well-formed, and we're going to build it in order to run test cases. In this environment we fully expect overload resolution to succeed on all method calls. The second is you are typing code in Visual Studio or VSCode or another IDE, and you want to get IntelliSense and error reports as you're typing. Code in an editor is almost by definition wrong; you wouldn't be editing it if it were perfect! We fully expect the code to be lexically, syntactically and semantically wrong; it is by no means exceptional for overload resolution to fail. (Moreover, for IntelliSense purposes we might want a "best guess" of what you meant even if the program is wrong, so that the IDE can help you correct it!)

I therefore designed the overload resolution code to always succeed; it never throws. It takes as its argument an object representing a method call and returns an object which describes an analysis of whether or not the call is legal, and if not legal, which methods were considered and why each was not chosen. The overload resolver does not produce an exception or an error. It produces an analysis. If that analysis indicates that a rule has been violated because no method could be chosen, then we have a separate class whose job it is to turn call analyses into error messages.

This design technique has numerous advantages. In particular, it allowed me to easily unit-test the analyzer. I feed it inputs that I've analyzed "by hand", and verify that the analysis produced matches what I expected.

Can we assume that the user entered the correct credentials and throw an exception when the credentials are invalid, or should we expect to get some sort of LoginResult object?

Your question here is about what I think of as "Secure Code" with capitals. All code should be secure code, but "Secure Code" is code that directly implements aspects of a security system. It is important to not use rules of thumb/tips and tricks/etc when designing Secure Code because that code will be the direct focus of concerted attacks by evildoers who seek to harm your user. If someone manages to sneak wrong code past my overload resolution detector, big deal, they compile a wrong program. But if someone manages to sneak past the login code, you have a big problem on your hands.

The most important thing to consider when writing Secure Code is does the implementation demonstrate resistance to known patterns of attack, and that should inform the design of the system.

Let me illustrate with a favourite example. Fortunately this problem was detected and eliminated before the first version of .NET shipped, but it did briefly exist within Microsoft.

"If something unexpected goes wrong in the file system, throw an exception" is a basic design principle of .NET. And "exceptions from the file system should give information about the file affected to assist in debugging" is a basic design principle. But the result of these sensible principles was that low-trust code could produce and then catch an exception where the message was basically "Exception: you do not have permission to know the name of file C:\foo.txt".

The code was not initially designed with a security-first mindset; it was designed with a debuggability-first mindset, and that often is at cross-purposes to security. Consider that lesson carefully when designing the interface to a security system.

It doesn’t matter one bit how long the call stack is.

Method A calls method B which could throw an exception. Method A has three choices: It can be written in such a way that it can let an exception pass through to its own caller without code handling it at all. Or it can catch the exception, handle it completely and not pass it on - that’s what you do if you know how to handle the exception. Or it catches the exception, takes actions to make its own code work fine, and retries the exception, possibly modified. That’s what you need to do.

Now if you have a long call chain, that just means that you may have more methods that can throw exceptions. You need to do the steps that I described in each method that calls another method that can throw.

Important: Any method that has no exception handling code must be written in such a way that everything works fine if an exception is passed through. That’s the developer’s job. Garbage collection in Java and destructors for stack variables in C++ help.

Us usual, there is no single best way.

What IntelliJ suggests (and it offers more options than just adding it to the method signature) are only ways that are simple mechanical fixes.

We'd need to more know about your project, your architecture, etc. to determine what the best approach for your software, given your current knowledge would be. That approach may change tomorrow though when you learn something new or get other requirements.

Generally, I commend you for recognizing the simple solution as a bad idea. Yes, just adding throws declarations to hundreds of methods certainly isn't a very appealing solution. In order to find other approaches to error handling, there are a few guiding questions you can ask:

- What sort of error are you thinking about here? Is it an inconvenience, does it reduce the service's capabilities, does it outright crash and stop your software from working,...

- Who is this error relevant to? Is it something the user needs to see, or something that operations needs to know about, or will only developers be interested in it?

- How should the error be treated? Is it enough to just catch an exception and do some logging? do you need to dynamically modify your program behavior (f.ex. to work around a 3rd party service being offline)? do you need to translate your error into some other domain (f.ex. turn an authorization-related exception to the proper HTTP error code)

After you got an idea to the answers for these questions, there's a whole other bunch of questions you can ask to narrow down the best technical solution. Read up on different error handling approaches if you don't already know a bunch of them - here's just a starter: Validation/Either objects (or more generally monads), HTTP filters, checked or unchecked exceptions, ... and then there's a whole line of thinking on how to design your programs such that things you thought about as "error" become normal and need not even be treated in any exceptional way.

I'm building a backend java service in an enterprise setting. There are a few errors I know the application will throw so I've caught them in the code and am logging an error level message with a bit of information about the transaction that caused the error.

I'm wondering if this is the best option or if I should also be throwing the error. Our APM (dynatrace) does not have application log access so I'm assuming it won't know about log messages even if they are errors but I have yet to confirm this with the necessary people at my org. Ideally I want dynatrace to know when these errors are occurring so it will reflect in the reported application error rate.

Edit: secondary question that comes up as I think more about this and get replies...should error level log statements contribute to dynatraces error rate metrics? I would hope so but it's my first time using it so just want to make sure my assumptions are right.